A book was published by, the economist, physicist, mathematician and computer scientist John von Neumann which became a sensation, at least among mathematicians – Theory of Games and Economic Behavior. This volume is written with the help of a colleague, Oskar Morgenstern, it is of nearly biblical proportions is so dense and littered with mathematics that only a game-theory specialist could understand it and some of them struggled.

Even so, game theory has spread far beyond the boundaries of mathematics to become a valuable tool for explaining human behavior. This theory is one of the theories that have been used by diplomats, biologists, psychologists, economists and many others in business, research and global politics.

Game theory is also used as a tool for parents. Children can be tough negotiators, as parents know. And the stakes are high: the outcome of negotiations between parents and their children can affect a family’s happiness and the children’s futures.

In spite of having these complicated mathematics, game theory is simple to explain: it’s the science of strategic thinking. Talking about Game theory, it does not cover all games, but only those in which an opponent’s or negotiator’s strategy affects your next move. It has nothing to do with solitaire, in which your ‘opponent’ – a deck of cards – has no strategy. If a beautiful example of game theory is to be taken then it should be Chess, where two crafty strategists are continually trying to anticipate and block the other’s likely moves.

One of the other subjects of game-theory research is the auction and is useful for parents. Suppose your children all want to control the TV remote. Set up what’s known as a sealed-bid, second-price auction. Each secretly writes down what he or she is willing to pay. When the papers are opened, the highest bidder wins the right to buy the remote at $1 plus the second-highest bid. It’s said that it is far superior to a coin flip because the person who most wanted the remote got it.

Game-theory deals depend upon fairness and, often, so do dealings between parents and children. Children are consumed with the idea of fairness. If a candy bar is to be shared by two and unfortunately isn’t broken exactly in half, the one who gets the smaller piece will howl. Game theory offers parents a way around this.

Suppose you break the candy bar into two pieces that are almost the same size, but not quite. And it is identifiable by your children. Something that can be done and also that seems eminently fair is tossing a coin. Your children can recognize the fairness in tossing a coin; nobody controls the outcome. What could be simpler? You toss the coin into the air. The winner gets the slightly bigger piece of candy; the loser gets the other. But when the coin hits the floor, something changes. What happens now is that the winner believes the decision was completely fair; the loser demands that he get a do-over. To him, it doesn’t seem fair at all.

The problem here turns on the meaning of fairness. The coin toss is fair, as we usually understand that. So what is the problem? In game-theory terms, the outcome was not envy-free. The loser desperately envies the winner. It’s not a very satisfactory solution for you or for one of your two children.

Here’s a way to get a much better outcome. Suppose you have the remains of a birthday cake you want to divide between your two children. There arises the same problem as it was there with the candy: it’s difficult to cut two equal pieces. So you turn to the technique we call ‘I Cut, You Pick’: your daughter cuts the cake, and your son picks the half he wants.

While cutting the cake your daughter will be as careful as possible to cut it into two identical halves to get an equal one otherwise she will get the smaller one. As it is difficult to cut the cake into two exact halves, you designate your son to make the cut the next time you have cake. And you continue to take turns. This is fair, and game theory shows that people will recognize it to be fair. It’s far superior to the brutal coin toss.

Game theory can also be used as a way for the family to decide where to go on vacation, what to have for dinner; how siblings can learn to cooperate without mum or dad’s intervention – and many other problems that routinely turn up in the family.

It is truly said nowadays that Game theory is a gift of evolution, which sculpted us to behave according to precise and illuminating mathematical rules. We use it all the time. Game-theory parenting is a new way especially researched to help parents explicitly understand the rules and reflect on what the rules say about raising healthy and successful children. If we understand game theory, it will help us to become the parents we were meant to be. It is almost said that Parents and children will not be able to make their way through von Neumann’s often opaque book, but they don’t have to. They are all game theorists already. All they need are a few good rules. And that’s what game theory provides.

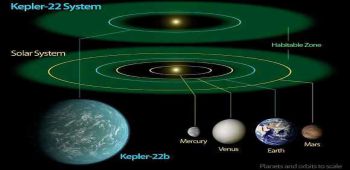

Second Solar System ..

Second Solar System ..

A Crazy Chapter Of H..

A Crazy Chapter Of H..

Want To Be A Better ..

Want To Be A Better ..

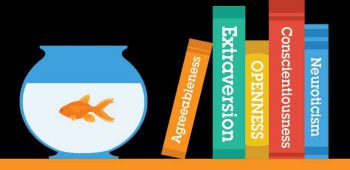

Personality Traits &..

Personality Traits &..

Are Animals Born Wit..

Are Animals Born Wit..

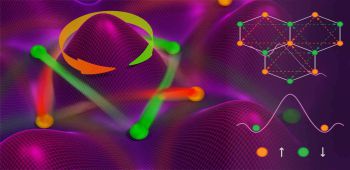

Atomic Spins Evade H..

Atomic Spins Evade H..

Weighing A Thought..

Weighing A Thought..

Can Spinach Be Used ..

Can Spinach Be Used ..

Comments